Battle Over Hetch Hetchy: Commoditization and Human Apathy

- Griffin Reilly

- Jan 26, 2021

- 4 min read

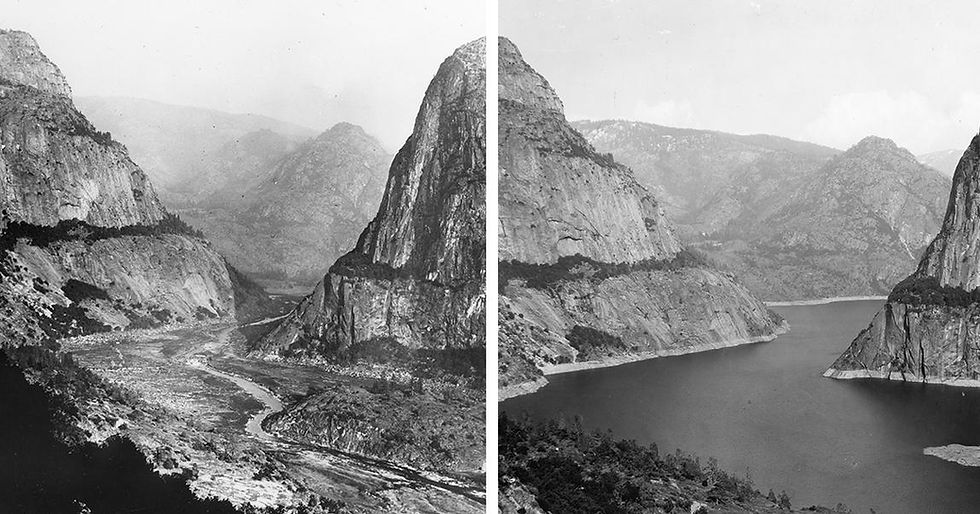

Robert Righter’s The Battle over Hetch Hetchy illustrates how the Hetch Hetchy Valley fell victim to capitalist destruction after decades of corrupt politics and unequal distribution of resources in nearby San Francisco. But at the heart of that long string of events is the average American’s relationship with nature: an aside to or brief escape from their normal lives. Early conservationist efforts to defend Hetch Hetchy echoed that sentiment, and argued the valley should be preserved for its economic potential as a tourist destination, rather than for the sake of the land and environment itself.

Camping, hiking, and outdoor recreation became popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, as the industrious and labor-intensive daily schedule of city life led to an anxiety and stress in its citizens. Places like Hetch Hetchy or Yosemite became resources of their own to resolve these stresses among city-dwellers—many sought a retreat to nature as a way to cleanse the mind. “Those who fought for Hetch Hetchy always praised the valley as a scenic place to camp…in the words of historian Cindy Aron, ‘camping seemed to fit perfectly the needs of a growing vacation public. It promised health, rest, and enjoyment—all for a modest price,” writes Righter (page 25).

But this urge to immerse oneself in nature only went so far for the average San Franciscan, Righter continues. “Many avid readers of Muir enjoyed his words and books from the comfort of their home hearths, experiencing the wilderness through Muir’s rapturous descriptions and harrowing tales. Few wanted to experience firsthand what Muir could give them vicariously,” he writes (page 26).

Even though this trend increased the public appreciation for nature, it was still barely more than an urge to use the land for a specific resource. This flawed approach still viewed the land’s beauty as a commodity that could be altered for that human requirement just as any other physical resource.

It should be noted that places that weren’t blessed with the same criteria for natural beauty would have never been given the opportunity for its fate to be a subject of debate. When land had no “scenic value,” its existence as a National Park was far less sacred. The United States has a history of never preserving land for the sake of itself, insists Righter, rather only if it presents a specific resource for humans. “The engineers ignored the national park status of Hetch Hetchy and gave no real weight to scenic value. Given the criteria they established, their conclusion to allow construction was self-evident,” (page 116). In fact, city officials arguing in favor of the creation of the reservoir went so far as to demean the current (at the time) valley’s beauty; the addition of water, they said, could actually enhance its appearance, which was otherwise bland. The Freeman Report, in fact, was as far as to describe the valley as insufferable, “once there, one either was too hot or was plagued with mosquitoes.

In other words, not only was the unimproved Hetch Hetchy Valley expensive to visit, but it was not a pleasant place for humans and never would be unless transformed,” writes Righter (page 103). This faux appreciation for land’s beauty was ultimately one of the biggest weapons used in the fight against Hetch Hetchy’s protection.

While early conservation efforts were still largely focused on how to best commoditize nature for tourist consumption, things in government quickly changed to focus on the true protection of forests. Though a bit too late, it proved that people eventually learned how Hetch Hetchy was handled improperly, and the government agencies that oversaw the National Parks and the interior would change in the following years. “They wished to create a federal agency that would view land and water and mountains with a different mission than those of the Bureau of Reclamation and U.S. Forest Service, both of which emphasized the commodity value of natural resources,” says Righter (page 193). Thankfully, these flaws in the abilities and focuses of the federal conservationist agencies over time were highlighted and dealt with, much to the credit of decades of influential writing and encouragement from John Muir.

Other than general human apathy towards nature and a misguided forest service, the corruption of San Francisco’s government and water services played a huge role in Hetch Hetchy’s destruction. Seeing the earthquake, California senator Key Pittman wrote “I saw such suffering as I never expect to see again, and I know that a lot of it was caused by reason of the inefficient system of water that was being supplied to the people of San Francisco,” (page 60). For decades, politicians and business leaders knew just how valuable of a resource water was, and maintained power by strategically wielding it, rather than coming together to make it a goal to provide the resource (a human right) to everyone equally. So when the earthquake struck, it exposed this flaw in local government. Leaders then seamlessly channeled this public outrage into the final blow to those who had been defending the use of Hetch Hetchy as a reservoir.

In conclusion, Robert Righter illustrated in The Battle over Hetch Hetchy how a life in or appreciation of nature and its beauty was a rarity or occasion for the average San Franciscan. For conservationists who promoted Hetch Hetchy’s preservation, their argument was still one that prioritized tourism as an alternative source of income.

This is not to belittle the importance of what conservationists were aiming to achieve, rather to underscore the way in which their cause was only ever presented as how the land would be used in relation to human society. Either it would be used for man’s recreational enjoyment or it would be used for its physical resources to develop societies far away; preservation was never considered necessary for the good of the land itself, rather only ever how it could be used best by humans.

So eventually, when the need for water in San Francisco and its surrounding areas became an absolute necessity following the destruction of 1906, there wasn’t even a choice to be made.

Hetch Hetchy in 1917 (left) and after becoming a reservoir in 1933. Photos courtesy of SF Chronicle.

Referenced in text is Robert Righter's 2005 non-fiction book "Battle Over Hetch Hetchy."

Righter, Robert. "Battle Over Hetch Hetchy." Oxford University Press. 2005.

Comments